The airport environment is a notoriously tough playing field for any company to turn a profit, much less a startup. Most vendors at the airport (e.g. restaurants, shops, kiosks) operate on thin margins as they have to concede the majority of their earnings to the airport under tough profit-sharing agreements. The limited number of high-traffic airports around the world creates a unique oligopoly, if not even a monopoly, as only the biggest metropolitan areas have multiple airports competing with each other. Therefore, young digital challengers aiming to enter this ecosystem have little-to-no bargaining power.

Despite this hostile environment, many entrepreneurs continue to venture into the airport space, seeing an opportunity to improve what can often be a very frustrating place for travelers.

One of the startups eagerly addressing traveler needs at airports recently died

Until this year, one of the most promising startups innovating the airport experience was Europe’s FLIO – an airport app offering navigation, flight tracking, Wifi access, restaurant vouchers and more for hundreds of airports around the globe. But in late July 2019, Stephan Uhrenbacher, serial entrepreneur and the founder of FLIO, announced on his personal blog that the company had sold off its assets, effectively shutting down operations. In an honest letter worth further reading, he disclosed the factors that led to this inevitable end and why his seventh company became the first on his track record not to return a profit for its investors.

If not even “the world’s most used airport app” was able to survive, what’s the necessary scale for startups to survive and prosper in the airport context?

Scouting all startups in the airport environment

To gain more insight into this topic, we started compiling a list of all airport startups founded since 2010, collecting only those that remain independent and private to this date (thus excluding any companies that have been acquired). We also decided to specifically exclude firms mainly focused on airport transfer offerings, e.g. Mozio, Talixo or Blacklane, as we see the airport transfer category as more closely related to the overall New Transportation space, which includes ride-hailing, car-sharing, carpooling, and others. For a full overview of all New Transportation categories, check out our New Transportation Leaderboard.

It’s also worth mentioning that we excluded those startups that predominantly address services more closely connected to airlines (e.g. flight tracking, last-minute upgrade bidding, flight cancellation aid, and much more). Even though these services and apps are also most often used while travelers spend time at the airport, this wider definition would go beyond the scope of this article and needs to be analyzed in a separate piece. Hence, we concentrated on only those startups that fully focus on the direct airport experience.

Here is our comprehensive mapping of airport startups based on the above criteria

For more detailed information on all the startups listed in our infographic, check out the Airtable view at the bottom of this article.

What does the infographic tell us about the airport startup landscape?

VC funding is scarce

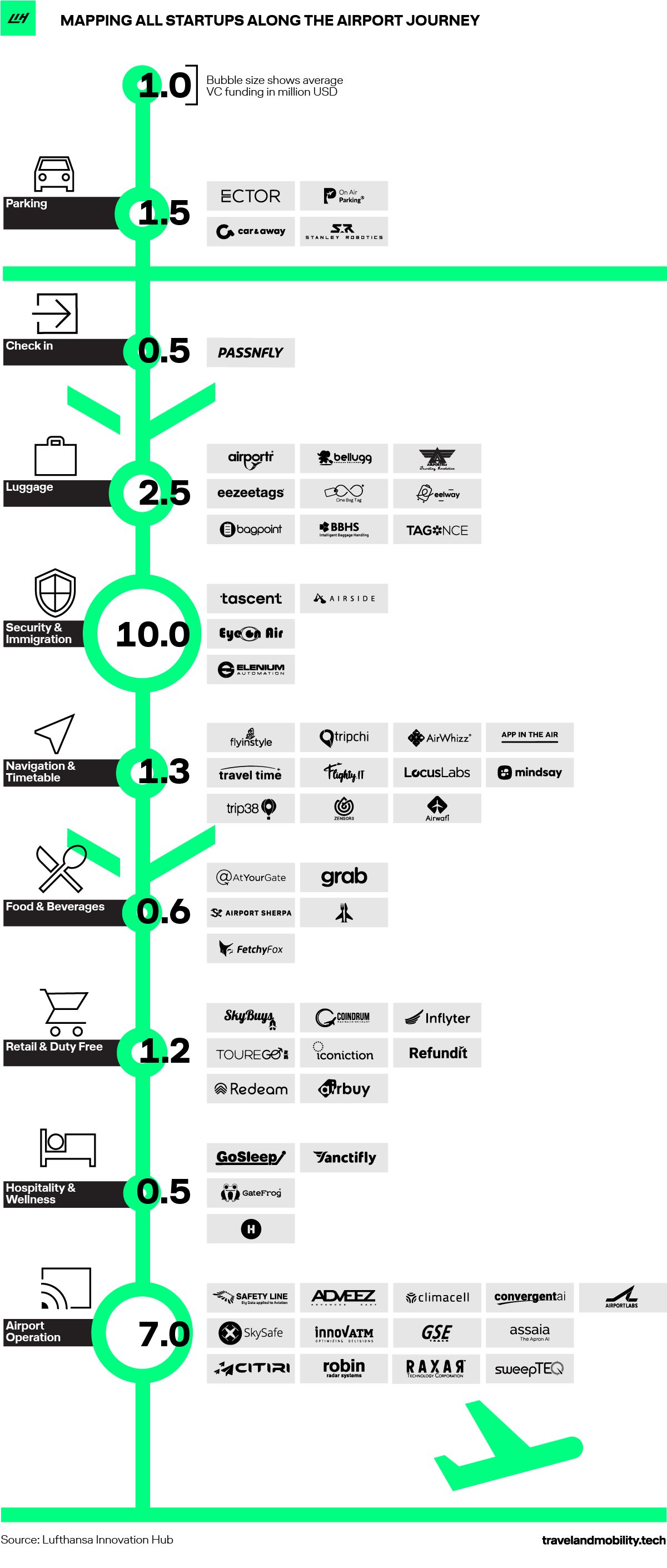

Looking at this list, what strikes us is a significant lack of Venture Capital (VC) funding across the board: out of the 60 startups, only four raised more than EUR 10 million in VC funding (AirPortr, ClimaCell, SkySafe, and Tascent), with only five ventures having raised any type of VC round within the last 18 months (AirPortr, AtYourGate, Bellugg, Elenium Automation, Innov’ATM, and Rejjee).

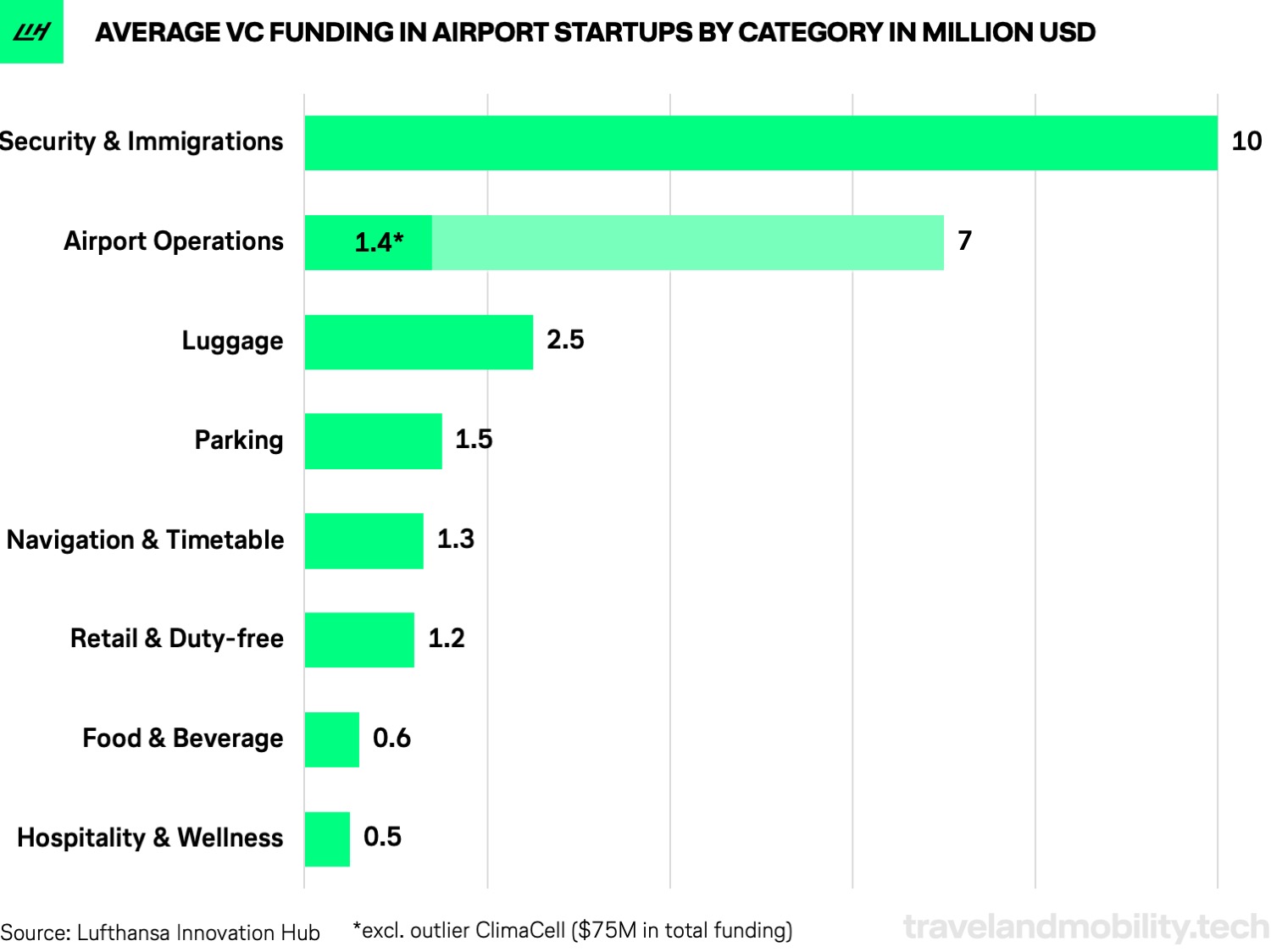

Moreover, funding is also noticeably unevenly distributed across the different categories the startups operate in. For instance, startups in the security and/or customs & immigration space received more than EUR 10 million in funding on average, while startups in airport operations such as ground handling received only EUR 7 million on average. Luggage-focused ventures collected even less with only EUR 2.5 million.

It’s important to mention that the outliers in our startup sample significantly skew these averages, e.g. if ClimaCell (total funding of EUR 70 million) had been excluded from our list, the airport operations category would have only raised EUR 1.4 million on average, falling behind the smart-parking sector.

In short, airport startups across the board lack VC support as investors seem to forgo this space (more on this below). In the rare occasions where they do invest in airport startups, those innovating the security/customs and immigration check seem to promise the most potential.

How can this be explained?

The scarcity of VC funding for startups in the airport context is an atypical observation in these times, where funding dynamics across the startup landscape are going through the roof (read our VC report on The State of Travel & Mobility Tech to learn more).

But the airport environment is a challenging playing field with most investors hesitant to fund startups even if they address major pain points that are impossible to overlook when going through an airport (e.g. waiting times, limited information on flight delays, etc.). The major reason for investors’ reluctance is arguably the limited growth path and scaling potential of startups in this highly regulated and controlled environment (we’ll explain below).

To find out more about why the airport is such a difficult and challenging playing field for startups, we talked to the innovation units of four international airports: London-Gatwick, Munich (Terminal 2, a joint venture by Munich Airport and the Lufthansa Group), Paris (operated by Groupe ADP, which runs Charles-de-Gaulle, Le Bourget, and Orly) and San Diego.

Combining their experience with our own insights, we came up with the following explanations:

#1 – The global airport landscape is an oligopoly

In the U.S., there are less than 30 airports serving more than 10 million passengers annually. In Europe, there are 51; in Germany, 8. This leaves only about 80 major airports to serve in the Western world. What’s more, many airports in Europe are operated by the same company such as Groupe ADP, which operates the three major airports of Paris (Charles de Gaulle, Le Bourget, and Orly), and FBB, which operates all airports in Berlin (Schönefeld, Tegel, and Berlin-Brandenburg – still under construction).

Moreover, retail and food spaces within airports are usually operated by large franchises as the industry has gone through some major consolidation since the early 2000s. Basel-based Dufry, the world’s largest duty-free operator, is present in 65 countries with over 2,300 stores after taking over World Duty Free, one of its main competitors, in 2015.

It is next to impossible for startups to negotiate attractive prices in this oligopoly. At the same time, the predominant players have no incentive to innovate and cooperate with outsiders as they operate in an ecosystem that doesn’t exhibit noteworthy competitive dynamics and is without any alternative for the traveler: if you want to take-off from a specific city, you have to use its airport. FLIO learned this lesson the hard way when negotiating with large, global airport retailers. They just weren’t willing to pay a small startup for their services.

In summary, today’s airport retail space is characterized by a unique comfort level. External pressure for airport operators and vendors to truly innovate is de-facto non-existent. While there is a brick-and-mortar retail apocalypse afflicting large chunks of the industry – with retail chains going bankrupt at a furious pace – stores in airports celebrate solid growth rates. It’s not surprising, as airport-based retail has some significant advantages over its non-airport-based counterparts:

- no e-commerce/Amazon effect (yet)

- growing foot traffic, as total passenger numbers are expected to rise to 4.6 billion in 2019, up from 4.4 billion last year

- and 365 days of operations with weekends and holidays among the busiest times out of all

As a result, well-run airports can earn attractive margins. But airport operators tend to use their dominance to their advantage, leaving especially smaller retail vendors little profit after paying the airport their due. Hence, vendors themselves have little room to pay startups for any services they might bring to the table.

This means that startups have a much better chance of getting into the airport if they operate under a profit-sharing agreement with the airport directly, thereby increasing the airport’s revenue. However, here they risk falling into the same low-margin trap as many other vendors before them. And again, it’s hard to find a value proposition incentivizing an airport to open up its sacred space for external digital entrants.

#2 – Sales cycles with airports are long-winded

Securing a contract with an airport can easily take more than a year – a lifetime for most startups. Lengthy negotiations and extensive security checks are the norm due to the highly regulated world of air travel (more on that later). These challenges are even more severe in the United States where all airports are generally owned by the state or federal government (with the sole exception of Branson Airport in Branson, Missouri, which is owned and operated by a consortium of private investors). Essentially, all contracts with U.S. airports are government contracts and thus subject to special scrutiny and complexity.

The same is true for China, where airports are government-owned with one exception: the SF International Airport in Ezhou, Hubei Province, which is operated by the logistics firm SF Express. The fast validation of early MVPs, the default operation mode for most startups, becomes extremely difficult when government regulations get involved.

Moreover, early-stage startups with tight budgets don’t have years to spend on educating, signing, and onboarding their first handful of clients. Another complication is that since airports usually grant contracts for five years or more, they might be hesitant to sign with startups as there’s no guarantee they’ll be around in five years. In conclusion, both sides struggle with each other’s mode of operation.

#3 – Airports choose big tech players over small startups

The IT and tech incumbents traditionally supplying airports don’t rest on their laurels either. In many cases, they’re the ones leading digital innovation at the airport. Looking at China, we can see clearly that Chinese airports are well ahead of the rest of the world. Here’s an example: last year, Shanghai’s Hongqiao International Airport launched an automated security clearance system based on biometrics. In terminal one, Chinese ID cardholders can pass through a fully automated security clearance area in less than 12 seconds. This is only the start of a plan to make the entire airport process unassisted, from check-in and security check to boarding.

In many of these initiatives, airports are entrusting big tech players with the upgrades. Alipay and WeChat lead the VAT refund for Chinese travelers, while Huawei is the main actor in the smart airport project at Shenzhen’s Bao’an Airport.

Because most airport innovation is incremental, tech incumbents have a significant advantage over startups, with state-of-the-art technologies ready-to-go as well as a proven track record of safety and reliability. This is crucial in so many areas of the airport. Many of these larger tech companies can also provide all-in-one solutions, allowing the operator to run all safety-critical systems with a single partner.

#4 – Regulations are strict

We’re all familiar with the justifiably high scrutiny at airport security checkpoints. Startups often have to go through similarly tedious monitoring processes by government bodies and airport operators if they seek to roll out their products and services on airport premises. While this is a necessary step to ensure flying stays safe, it significantly hinders the experimentation – and ultimately – the adoption of new technologies. In particular, startups working on safety-related areas such as ground handling or security clearance sometimes fail to present the required safety certificates. U.S. airports often struggle to tender contracts with foreign companies, a process further complicated by the limitations of government contracts.

But while regulations make life hard for some startups, they can also open the playing field for others. For example, after 9/11, a federal ban was issued on luggage storage at the airport. As a result, a series of startups began offering luggage pick-up and delivery to and from the airport, storing the baggage off-premise.

Perhaps due to these and other complex factors, startups in the airport space seem to flock to some areas more than others. Below, we examine some of the reasons for this behavior.

Why are some airport startup verticals so crowded?

Again, regulation is one answer to this question. As shown in the examples above, the regulatory environment of the airport might favor one vertical while effectively making it impossible to operate in others.

As metropolitan airports fight with traffic congestion at peak hours, they look to startups for a solution. Ridesharing, carsharing, and airport transfer booking platforms in particular are forming in larger numbers than most other verticals. Similar developments can be observed for the smart parking sector. Airport parking is among the main non-aviation revenue sources for airports, often even the principal one. While startups in the beginning sought confrontation and tried to steal this chunk of business from airports, nowadays their relationship is often characterized by collaboration rather than competition. For example, carsharing providers Car2Go and DriveNow (recently united under the new brand ShareNow) as well as Sixt Share and Miles Mobility are currently collaborating with all major airports in Germany instead of aggressively pursuing competition.

Startups and airports need to reconcile their differences to improve the travel experience

With some verticals apparently seeing promising innovation, how can airport startups finally start to fly across the entire airport arena? One way is to find business models that allow startups to approach the airport operators with a revenue-sharing proposal, potentially boosting their top line instead of billing them for services. An example of this can be seen in the luggage sector. Here, startups charge the traveler for storage or delivery while participating airports receive a share of the profit.

Another way is to participate in one of the growing number of airport incubation and acceleration programs – ideally with a group operating multiple airports – giving the startup access to a critical mass of customers. One example is the Innovation Hub of Groupe ADP. Because it operates three major airports under one company, Groupe ADP can offer startups a significantly larger customer base than a single airport. As discussed above, this critical mass of customers is usually tough to reach with traditional sales approaches.

The third recommendation for startups is to focus on the airport as an additional distribution channel, not as the core market to roll out their ideas. A startup developing a product or service with an airport application should seek to sell to other customers first, coming back to airports when they have a solid product/market fit and can show first results. Many indoor mapping and navigation startups begin to invade airports only after building their products around similar environments with fewer restrictions, such as shopping malls, sports stadiums, or within production facilities and factories.

The timing is right

On the bright side, we currently see a very promising window of opportunity for airports and startups to re-activate deeper collaboration initiatives. In the past, startups have often had a tough time building their digital offerings on top of existing, legacy technology systems at airports (the same is true for airlines by the way). But with so many brand-new airports being built around the world these days, this presents a great chance to establish totally new technology standards that allow startups to better connect and integrate with airports.

On a similar note, technologies that have the potential to reshape passenger experiences at airports exist. But they need to be fully leveraged. Many airports have started experimenting but we are far away from a significant leapfrog. One example: according to The Future is Connected report by SITA, 83% of passengers today carry smartphones; given this, it is imperative that airports connect with passengers through their smartphones. Beacon based proximity marketing is one such technology potentially helping create enhanced end-to-end experiences at airports, seamlessly through passengers’ smartphones. Powerful real-world applications would include wayfinding, flight information, baggage collection, measuring the distance to the gate, offering loyalty programs and conveying duty-free promotions among others.

Long story short: what will change for travelers?

Unfortunately, for now, it looks like we will have to remain patient. The airport experience will not change drastically anytime soon. But are the airports solely to blame for this? Not exactly. The industry’s natural risk aversion is fundamentally misaligned with the uncertainty-embracing nature of the startup world.

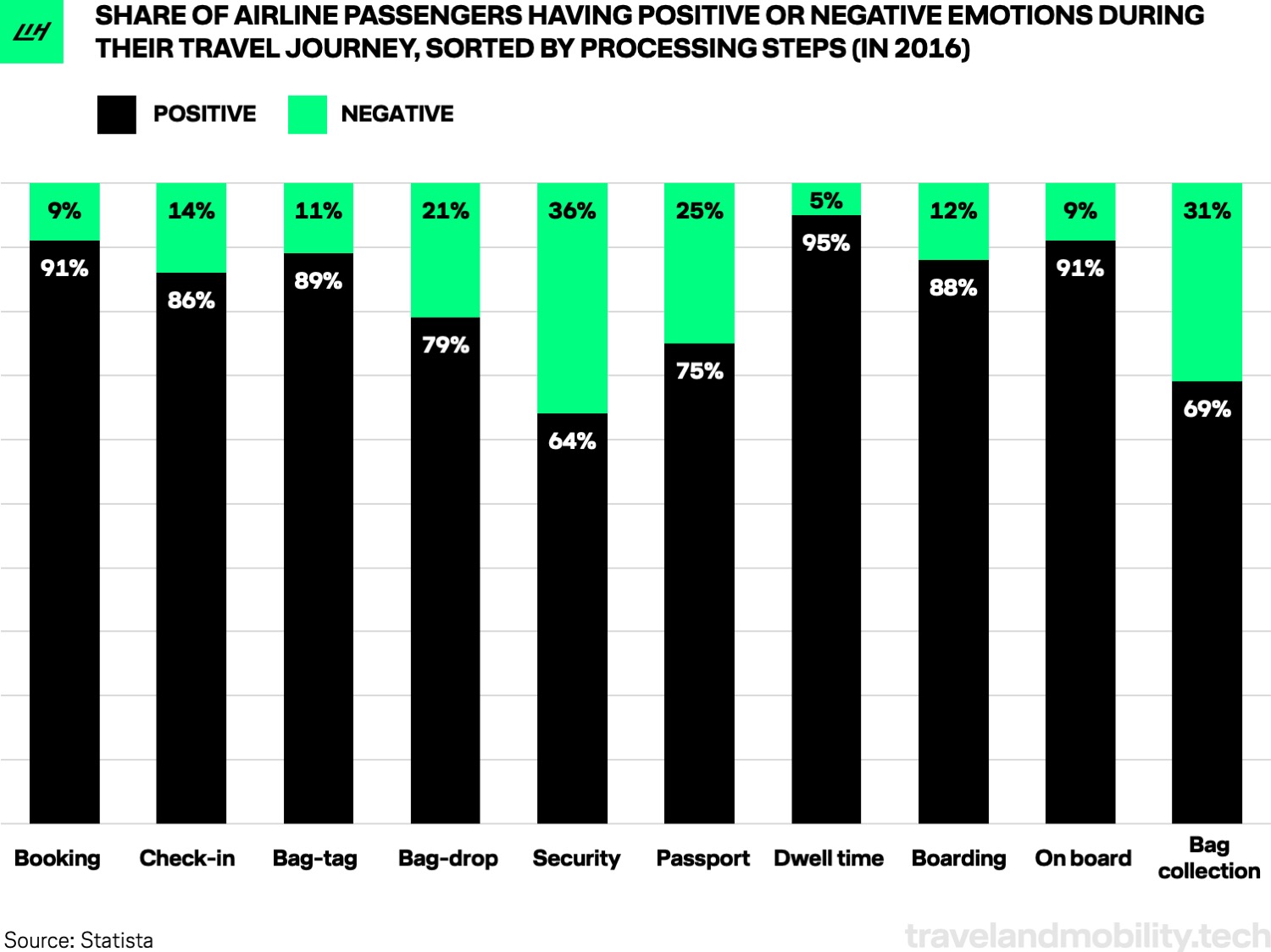

Moreover, it’s difficult to reconcile the classic VC model, which focuses on hyper-growth and USD 100m+ exits within a five to ten-year timeframe, with the reality of long sales cycles and extensive testing stages in the airport market. Until startups and airports learn to work together to accommodate these differences, travelers will continue to experience discomfort along their airport journey.

The good news: startups will continue venturing into the airport environment. Founders often draw business ideas from their own experiences and the pain points they observe in their everyday life, e.g. while traveling. Today’s painful airport experience is something a lot of people will continue to relate to, and strive to fix. The big question remains whether startups and airports will find common ground to effectively collaborate. Indicators let us believe that the right timing for this is now.

Full company list: